Emerging market exchange rates can be catalysts of self-reinforcing trends. Currency appreciation raises both global lenders’ risk limits and EM institutions’ debt servicing capacity. Currency depreciation spurs the reverse dynamics. Their escalatory potential constrains central banks’ tolerance for exchange rate flexibility.

Hofmann, Boriz, Ilhyock Shim and Hyun Song Shin (2016), “Sovereign yields and the risk-taking channel of currency appreciation”, BIS Working Papers, No 538, January 2016 http://www.bis.org/publ/work538.htm

Kliatskova, Tatsiana and Uffe Mikkelsen (2015), “Floating with a Load of FX Debt?”, IMF Working Paper, WP/15/284, December 2015

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/cat/longres.aspx?sk=43502

The below are excerpts from the papers. Some technical acronyms have been replaced. Headings, links and cursive text have been added.

The risk taking channel of EM FX trends

“Traditional arguments [suggest]… that currency appreciation is contractionary. An appreciation is associated with a decline in net exports and a contraction in output, other things being equal…Unlike the traditional model, the risk-taking channel can render a currency appreciation expansionary through loosening of monetary conditions. The risk-taking channel operates through the balance sheets of both borrowers and lenders. For borrowers who have net liabilities in dollars, an appreciation of the domestic currency makes borrowers more creditworthy. In turn, when borrowers become more creditworthy, the lenders find themselves with greater lending capacity.”

“The risk-taking channel of currency appreciation…operates through the supply of dollar credit.

- In the presence of currency mismatch, a weaker dollar flatters the balance sheet of dollar borrowers whose liabilities fall relative to assets… For EM borrowers who have borrowed dollars but hold local currency assets, the valuation mismatch comes from naked currency mismatches. For EM commodity producers, the valuation mismatch comes from the empirical regularity that commodity prices tend to be weak when the dollar is strong…

- Credit supply to corporates in dollars expands as a consequence, expanding the set of real projects that are financed and raising economic activity, thereby improving the fiscal position of the government…

- From the standpoint of creditors, the stronger credit position of the borrowers creates spare capacity for credit extension even with a fixed exposure limit…Banks lend to corporates subject to a Value-at-Risk (VaR) constraint…The global lender is a bond fund manager who can diversify across many EM sovereign borrowers… In a period when the US dollar is weak, the risk-taking channel operates across the set of EM economies, and a diversified investor in EM sovereign bonds sees reductions in tail risks, allowing greater portfolio positions for any given exposure limit stemming from an economic capital constraint. As a consequence, a weaker dollar goes hand in hand with reduced sovereign tail risks and increased portfolio flows into EM sovereign bonds…”

“However, when the dollar strengthens, these same relationships go into reverse and conspire to tighten financial conditions. Borrowers balance sheets look weaker. Their creditworthiness declines. Creditors’ capacity to extend credit declines for any exposure limit, and credit supply tightens, serving to dampen economic activity and the government fiscal position.”

“One explanation why countries may fear to let their exchange rates float is a negative influence of exchange rate volatility on…balance sheets. When they borrow in foreign currency while receiving income in local currency, exchange rate depreciation may lead to a sharp rise in debt-service costs, bankruptcies, and disruption of investment and consumption demand.” [*]

N.B.: Vulnerability to reversals in financial flows does not depend on current accounts and net capital flows but on the volume of gross foreign funding. Hence even EM countries with structural current account surpluses can be subject to self-reinforcing currency depreciation (view post here).

Empirical evidence

“The main predictions of the risk-taking channel are borne out in the empirical investigation for our spread-based measures of domestic monetary conditions as well as for bond portfolio flows…The empirical regularity [is] that currency appreciation often goes hand in hand with rapid credit growth on the back of more permissive financial conditions.

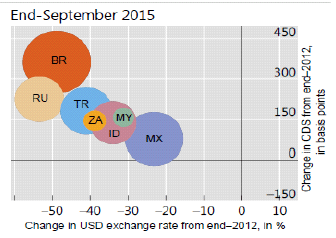

- Currency appreciation, defined as appreciation of an EM currency against the US dollar, is associated with the compression of the EM sovereign spreads and is accompanied by portfolio inflows into sovereign bond funds…A 1% appreciation of the local currency against the US dollar is estimated to decrease the 5-year CDS spreads by roughly 1.7 basis points. The effect is highly significant…There is both a time series and cross-section relationship between the CDS spread and the bilateral dollar exchange rate…In the cross-section… those countries that have depreciated more against the US dollar tend to have CDS spreads that are higher. Over time… as the domestic currency weakens against the US dollar, EM sovereign CDS spreads rise.

- Delving deeper, we find that these fluctuations in spreads are due to shifts in the risk premium, rather than in any deviations in interest rates already priced into forward rates.

- Investor flows in EM local currency bond markets increase when EM currencies appreciate against the US dollar…scatter plots reveal a negative relationship between EM currency appreciation against the US dollar and domestic interest rates…In short, when domestic interest rates rise, the domestic currency tends to depreciate. Conversely…when domestic interest rates fall, the local currency tends to appreciate against the dollar.

[On the influence of exchange rate volatility on local EM bond yields view post here.] - We examine the local currency risk spread measure due to Du and Schreger (2015), defined as the spread of the yield on EM local currency government bonds achievable by a dollar- based investor over the equivalent US Treasury security. The definition takes account of hedging of currency risk through cross-currency swaps. We find strong evidence that currency appreciation against the US dollar is associated with a compression of the Du-Schreger spread…estimates suggest that a 1% appreciation of an EM economy’s local currency against the US dollar decreases the local currency bond spread of a country by about 2.4 basis points…

- The expectations of interest rates already priced into forward rates are not significantly affected. These results suggest that the local currency sovereign spread is driven primarily by shifts in the risk premium and point to the importance of risk taking.”

“Crucially, the relevant exchange rate for our finding is the bilateral exchange rate against the US dollar rather than the trade-weighted effective exchange rate. Our results go away when we consider the orthogonalised component of the effective exchange rate that is unrelated to the US dollar; we and no evidence that a currency appreciation unrelated to the bilateral US dollar exchange rate is associated with loosening of financial conditions. Indeed, we actually find the opposite result for some measures of financial conditions… This is because the risk-taking channel has to do with leverage and risk taking, in contrast to the net exports channel which revolves around trade and the effective exchange rate.”

“The importance of the bilateral exchange rate against the US dollar stems from the role of the dollar as the international funding currency…The outstanding US dollar-denominated debt of non-banks outside the United States stood at USD9.8 trillion as of June 2015. Of this total, USD3.3 trillion was owed by non-banks in EM economies, which is more than twice the pre-crisis total.”

On the US dollar’s pervasive influence on EM financial conditions also view post here.

“[In] a set of 15 emerging market countries using monthly data for 2002-15…we find that policymakers react more to exchange rate movements – depreciations in particular – when FX debt in the non-financial private sector is high by using FX interventions and monetary policy rates. For FX interventions, we find that for every additional 10 percent of GDP FX debt in the non-financial private sector, the reaction to 10 percent depreciation increases by 0.2 percent of GDP. For monetary policy rates, we claim that 10 percent additional FX debt to GDP increases the monetary policy reaction to 10 percent depreciation by 0.08 percentage points in the next month and by about 0.2 percentage points cumulative over the following three months.” [*]

Quotes marked with [*] are from Klliatskova and Mikkelsen (2015). The majority of the quotes is from Hofmann, Shim and Shin (2016).