A paper by Greenwald, Lettau, and Ludvigson argues that short-term (quarterly) equity price fluctuation arise mainly from changes in risk aversion, while long-term trends (over decades) are heavily influenced by reallocation from labor to capital income. The latter appears to explain all the stock market gains in the U.S. since 1980.

Greenwald, Daniel, Martin Lettau, and Syndey Ludvigson (2014), “Origins of Stock Market Fluctuations”, NBER Working Paper No. 19818, updated draft December 16, 2014

http://www.econ.nyu.edu/user/ludvigsons/osf.pdf

The below are excerpts from the paper. Emphasis and cursive text have been added.

The economics of equity price factors

“The objective of this paper is…to study the primitive economic shocks from which all stock market fluctuations originate…Some economic shocks have tiny innovations [i.e. only small unexpected changes each quarter] but permanent or near-permanent effects on cash flows. Under rational expectations, permanent cash flow shocks have no influence on expected returns or the price-dividend ratio, but they can have a dramatic influence on real stock market wealth as the decades accumulate. On the other hand, fluctuations in expected returns may be associated with movements in risk premia and can persistently shift the real value of the stock market around its long-term trend. But because these fluctuations are transitory, their impact eventually dies out.

Stock market wealth evolves over time in response to the cumulation of transitory expected return shocks and both permanent and transitory cash flow shocks. “

The three primitive shocks

“The starting point of this paper is to decompose real stock market fluctuations into components attributable to three mutually orthogonal observable economic disturbances that explain the vast majority of fluctuations since the early 1950s. We then propose a model to interpret these disturbances and show that they are the observable empirical counterparts to three latent primitive shocks: a total factor productivity shock that benefits both workers and shareholders, a factors share shock that shifts the rewards of production between workers and shareholders without affecting the size of those rewards, and an independent risk aversion shock that shifts the stochastic discount factor pricing equities but is unrelated to aggregate consumption, labor earnings, or measures of fundamental value in the stock market.”

“The three mutually orthogonal empirical disturbances are obtained from co-integrated vector autoregression [a linear intertemporal model of economic time series]…Empirical disturbances are (i) consumption shocks…unforecastable movements in per capita consumption that may contemporaneously labor income and wealth changes (ii) labor income shocks…unforecastable movements in labor income holding fixed consumption, (iii) wealth shocks…unforecastable movements in financial wealth holding fixed both consumption and labor income contemporaneously… the particular ordering chosen would be the right one for uncovering the three primitive shocks of the model.”

N.B.: This model implies that all changes in financial wealth that are not forecast by past and present consumption and labor income changes and past financial wealth changes are wealth shocks. The paper calls these risk premia shocks. The term may conceal other wealth effects, however, such as those that arise from monetary policy, taxation, regulation and so forth.

The role of the three primitive shocks in stock market history

“We find that the vast majority of short- and medium-term stock market fluctuations in historical data are driven by risk aversion shocks, revealed as movements in wealth that are orthogonal to consumption and labor income…Although transitory, these shocks are quite persistent and explain 75% of variation in the log difference of stock market wealth on a quarterly basis…”

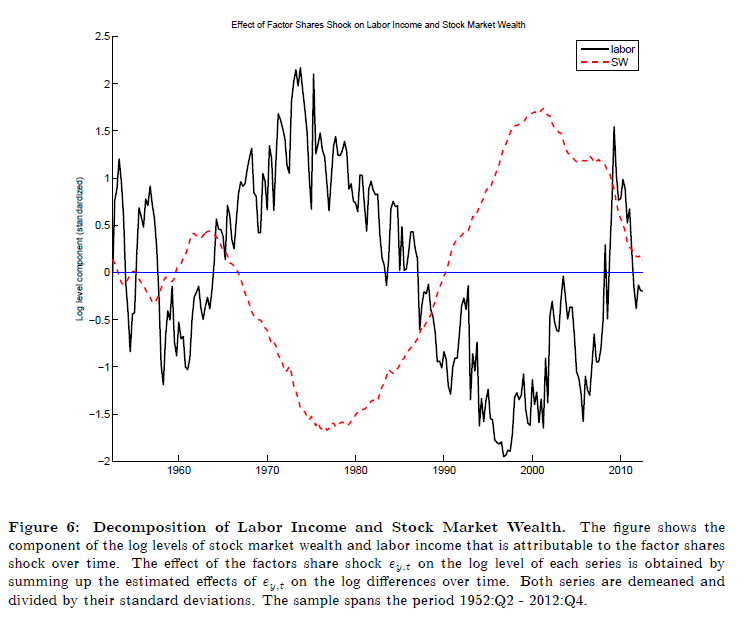

“At longer horizons, the relative importance of the shocks changes. Although the factors share shock explains virtually none of the variation in the real level of the stock market over cycles of a quarter or two, it explains roughly 40% over cycles two to three decades long. These facts are well explained by the model economy, which is subject to small but highly persistent innovations that shift the allocation of rewards between shareholders and workers independently from the magnitude of those rewards. By contrast, consumption shocks, both in the model and in the data, play a small role in the stochastic fluctuations of the stock market at all horizons.”

A narrative of equity valuation growth since the 1980s

“As an example of the magnitude of these forces for the long-run evolution of the stock market, we decompose the percent change since 1980 in the deterministically de-trended real value of stock market wealth that is attributable to each shock. The period since 1980 is an interesting one to consider, in which the cumulative effect of the factor shares shock persistently redistributed rewards away from workers and toward shareholders. (The opposite was true from the mid 1960s to mid 1980s.) After removing a deterministic trend, the cumulative effects of the factors share shocks have resulted in a 65% increase in real stock market wealth since 1980, an amount equal to 110% of the total increase in de-trended stock market wealth over this period. Indeed, without these shocks, today’s stock market would be roughly 10% lower than it was in 1980. An additional 38% of the increase since 1980, or a rise of 22%, is attributable to the cumulative effects of risk aversion shocks, while the cumulative effects of TFP shocks have made a negative contribution, a direct consequence of the large negative draws for consumption in the Great Recession. “